The NCUA board’s decision to merge the Temporary Corporate Credit Union Stabilization Fund (TCCUSF) into the National Credit Union Share Insurance Fund (NCUSIF) is a good idea.

The closure of the TCCUSF will reduce expenses, end contracts that at best perpetuate the continuation of misleading judgments, and create sorely needed transparency by simplifying the NCUA’s reporting.

More importantly, it should enable the NCUA to tie the financial results of the NCUSIF to real world events. What do I mean by that? Current practice involves projecting long term future facts to justify current expenditures factsthat simply don’t hold up when back-checked. Not even close.

This fresh start for the NCUSIF would also reinforce the NCUA’s primary fiduciary responsibility to credit union members. It is the members, after all, who send one cent of every insured share to fund the NCUSF, and for whose interests NCUA is thesteward.

Returning members’ money as quickly and as fully as possible should be the Board’s dominant priority.

Up to $2.4 Billion Of Your Members’ Money Is At Stake. Watch,Is The NCUA Finally Doing The Right Thing?

So, how much is due to your members? A lot more than NCUA staffers would like you to believe.

Make Your Voice Heard

The NCUA is accepting comments on the merger of the corporate bailout fund into the share insurance fund. The deadline is Sept. 5.

The merger of the TCCUSF and NCUSIF should allow for a distribution of a minimum of $1.8 billion and as much as $2.4 billion to credit union members in 2018. However, the NCUA staffers are making specious arguments to withholdalmost a billion dollars of your members’ money under the guise of risk management.

Today, all money in excess of the 1.30% equity ratio the regulator uses as its Normal Operating Level (NOL) must be paid back to credit unions in the form of a dividend. NCUA staffers are proposing to raise that ratio to 1.39% and tohold back funds in case the original assets of the TCCUSF which would now be a liability of the NCUSIF due to the merger do not perform as expected.

OK, sounds reasonable enough. Until one looks at the facts and does the math.

The justification for the increase is based on the same selective modeling that resulted in billions of excess reserves, unnecessary premiums, and overestimates of losses on legacy assets over the past seven years. Let’s dig into it. ContentMiddleAd

Hiding Behind a Wall of Words

To justify their proposal, the NCUA staffers presented the Board some 60 plus slides in my opinion creating more confusion for credit unions about financial judgments of the past nine years. This same pattern of multi-scenario modelingprojections, has been used to justify results that have proven time and again to have no connection to reality.

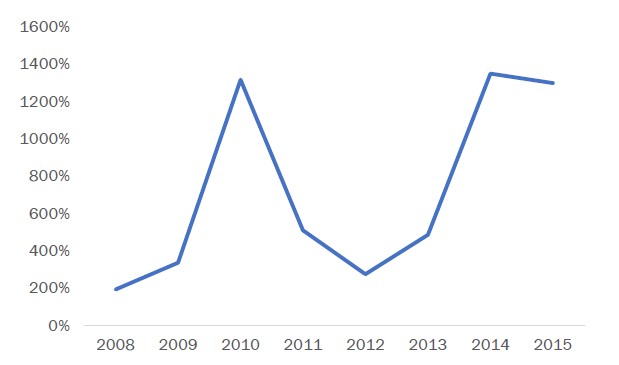

This pattern of significant erroneous loss projections is illustrated clearly in a nine-year table of the NCUSIF’s loss reserving activity compared with the reported net cash losses.

FACT: Throughout the Great Recession, the actual cash losses of the NCUSIF have only been a fraction of the reserves established at the prior year-end audit date. In 2009 and 2010 peak crisis years actual cash losses werejust 30% and 7.6% of the prior year-end audited reserves. (See graph below) By over-reserving, the NCUA not only charged credit unions unnecessary premium expense, but also demonstrated that its modeling and internal monitoring ofproblems are completely disconnected with real results.

I realize models are just that an attempt to understand different scenarios and chose the best paths today for an uncertain future. But with nine years of data, it’s clear that a new model is needed. If a credit union did this kind of modeling on its own loan loss reserves, there’s not a CPA in the country that would approve their statements.

FOLLOWING YEAR CASH LOSSES AS A PERCENTAGE OF LOSS RESERVE

Source: NCUA

Now, NCUA staffers want to use this same faulty reasoning to justify an increase of the NOL to 1.39%.

Let’s walk through the numbers using balances in both funds as of June 30, 2017. Today, the NCUSIF fund ratio is 1.26%. The NCUA’s own projections of a possible full-year loss of $26 million (versus actual midyear net income of $7.4million) won’t materially affect this level.

Adding the TCCUSF’s projected surplus to the NCUSIF’s current position of $13.026 billion gives a total balance of $16.0 billion. Using the NCUA’s own estimate of insured savings at year-end will result in a fund/insured share ratioof 1.47%, well above the current cap of 1.30%. At this fund size, each change of one basis point in the NOL ratio equates to approximately $109 million.

Therefore, staffers’ recommendation to increase in the NOL to 1.39% means holding back 13 basis points of TCCUSF surplus due to your members. That’s 4 basis points to meet the 1.30% current ceiling plus an additional 9 basis points for newcontingencies. This 9 basis point increase equals more than $980 billion (9 x $109 million).

Credit union members would only receive an estimated payout of 8 basis points (1.47%-1.39%), approximately $871 million. That would be about a third of the available TCCUSF recoveries transferred.

If credit unions received their total due 17 basis points above the current NOL of 1.26% they would receive approximately $2,400 for each $1.0 million of insured shares. Under the staff proposal, members will receive less than $900 foreach $1.0 million of insured shares. That’s a big difference.

Nine years of recent history has shown us that the NCUA’s models don’t match reality. They shouldn’t just keep relying on the same hoary projections that resulted in unnecessary premiums and billions in overestimates of losses forcredit unions during the corporate resolution to justify withholding members’ funds.

So, what’s wrong with reserving for contingencies? Nine years of recent history has shown that NCUA’s models don’t match reality. They shouldn’t just keep relying on the same hoary projections that resulted inunnecessary premiums and billions in overestimates of losses for credit unions during the corporate resolution to justify withholding members’ funds today.

From Insurance Fund to Slush Fund

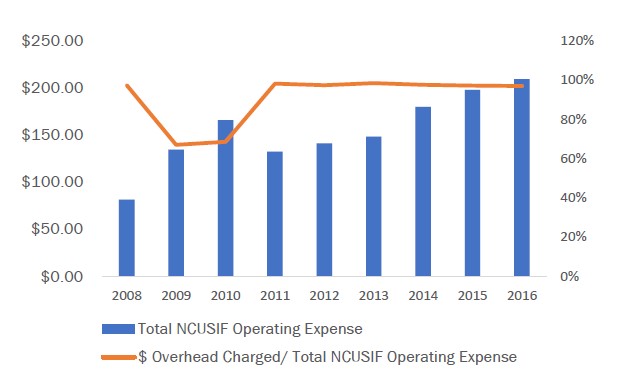

So, what’s their motivation? The NCUSIF is an insurance fund, designed in 1980 to provide capital support to credit unions in financial distress. However, over the past nine years, the NCUA has changed the role of the NCUSIF from an insurance fundto a slush fund for their daily operating expenses.

Each year, the NCUA charges the NCUSIF for a portion of its operating expenses. This is called the overhead transfer rate (OTR). Between 2008 and 2016, the OTR that is the proportion of operating expenses charged the fund, jumped from 52% to 73.1%.

This resulted in the entire increase in the NCUA’s annual operating budget (which grew by $123 million between 2008 and 2016) being billed to the NCUSIF.

The NCUA’s progressive raises in the OTR have resulted in an operating expense ratio that has risen steadily from 20% in 2008 to 91% of the NCUSIF’s total income in 2016. This current expense burden leaves little or no margin to pay lossesor to increase retained earnings to maintain the NOL ratio at the pace of insured share growth.

To top it off, after taking increasing amounts of NCUSIF income each year for expense reimbursement, NCUA continually shows no accounting correlation between the loss provision expense and the actual cash losses reported by the fund.

In 2009 and 2010, NCUA charged premiums which increased the fund’s total income by $1.657 billion. These two crisis premiums created the highest loss reserve in the agency’s history at $1.225 billion a reserve so excessive it could have paid for all the actual cash losses not only the following six years ($435 million), but also for all the losses paid by the fund in its history.

And what did NCUA do with the fund’s net in excess of the 1.3% ceiling? It didn’t give it back to credit unions. Rather, $462 million was paid into the TCCUSF. In other words, a premium charged for one purpose was then transferred to anotherfund which had a completely separate function. That is, NCUA kept the funds for themselves.

$ NCUSIF OPERATING EXPENSE VS. OVERHEAD RATIO

Source: NCUA

NCUA’s premiums to pay for these erroneous loss provision expenses were pro-cyclical with the economic crisis. This meant credit unions were over-assessed with an unnecessary expense burden at the very time they were trying to recover.

NCUA now maintains they must increase the NOL to 1.39% to avoid these pro-cyclical assessments. However, as the analysis shows, the problem isn’t either timing or adequate fund balances; the real problem is that the NCUA is unable to align financialcosts with the real losses in the field.

The latest example is from 2016. The actual net cash losses were $12.2 million, or just 6% of the year-end loss reserve. According to NCUA’s 2016 annual report (page 125), these same models are still in use today with the same staffdoing the projections.

In the request to raise the NOL, NCUA staffers say they included modeling based on the Federal Reserve inputs for a moderate and severe recession. Their model projects a five-year insurance loss between $1,266.6 billion (adverse) and $1,965.8 billion(severely adverse). Compare these forecasts to the actual losses of the past nine years (2008-2016) which include the worst recession since the Great Depression: $1,033 billion.

But Aren’t The TCCUSF’s Legacy Assets Riskier?

I’ve been asked: doesn’t the merger with the TCCUSF put more risk on the NCUSIF? Aren’t the legacy assets of the corporate system different riskier than that of regular credit unions? Isn’t that how we got into thismess in the first place?

Once again let’s dig into the numbers to show how the legacy assets are actually performing and what that means for the merged funds.

The NCUA’s models have been no better and in fact are quite possibly worse than their performance on the retail side. As in the NCUSIF, the agency’s TCCUSF record is one of overestimating losses, underestimating the value ofassets taken, and not providing timely and detailed information from which individual claimants and shareholders could monitor events.

To really follow all the numbers, one must look at five corporate balance sheets (pre-conservatorship), financial statements for the subsequent AMEs (asset managed estates), four bridge corporates financials, the 13 NCUA Guaranteed Notes (NGN) trusts,legacy assets spreadsheets, the TCCUSF financials and various reports the NCUA has issued to try to tie all of these separate entities together.

Putting aside the utter opacity in NCUA’s handling of the all these interconnected TCCUSF entities (which underscores the wisdom of merging the funds to increase visibility), NCUA itself says its initial projections of losses on legacy assets werein error by at least $3.2 billion or as much as $6.0 billion (slide 9).

NCUA staff’s recommendation is to hold back 4 basis points, or about $435 million, for the NCUSIF’s assumption of the TCCUSF’s contingent guarantee of the NGN payments.

This contingency was reviewed by external auditors of the TCCUSF fund as recently as December 2016. The following statements are from the KPMG audit:

- During 2016, the TCCUSF was principally responsible for guarantees related to the NGNs. As of December 31, 2016 and 2015, NCUA estimated no insurance losses from the NGN Program. (Page 3).

- The TCCUSF recorded no contingent liabilities on the TCCUSF’s Balance Sheet as of December 31, 2015 and 2016…there were no probable losses for the guarantee of NGNs associated with the re-securitization transactions. (Page 25).

One fact cited to support this zero contingency in the audit is that legacy assets’ net realizable value exceeded the remaining balances due to the NGN holders by $2.4 billion at year-end. NCUA’s rights as liquidating agent wouldpermit them to use the AME’s residual interests in the trusts to pay off the NGNs.

The only uncertainty is whether cash flow from legacy assets will be sufficient to make the final payments in 2021. However, the NCUSIF has extensive cash reserves. The holdback of 4 basis points or $430 million is not only unnecessary but is completelyunsupported by the two most recent audits.

The goal today is to convince credit unions that they need to stand up to the staffers at NCUA and demand the return of their members’ money. Merging the two funds will shed much needed light on the NCUA’s management of the corporate resolutionand hopefully, bring the industry closer to putting the trauma of the Great Recession behind us.

There are a host of additional questions about NCUA’s management of the TCCUSF, such as the allocation of legal recoveries, the $1 billion taken as losses on non-securitized assets held by the failed corporate credit unions, or whatthe $1.046 billion in liquidation expenses were for. But that is for another article.

The goal today is to convince credit unions that they must act as owners by responding to the NCUA board’s request for comments. Merging the two funds will shed much needed light on the NCUA’s management of future corporate resolution transactions.It will end a workout that has now gone on for almost nine years.

In summary, encourage the NCUA board to:

- Merge the TCCUSF and NCUSIF to increase transparency into how the industry’s resources are being managed;

- Keep the NCUSIF’s normal operating level between 1.2% and 1.3%; and

- Return more than $2.4 billion of members’ money to individual credit unions with a special dividend early next year.

Also Read

-

What’s $1.8 Billion Between Friends?

-

Is The NCUA Finally Doing The Right Thing?

-

Carpe Diem! NCUA Deadline Here For Comment On Bailout Funds Merger

Don’t Let The NCUA Take Your Members’ Millions (Again)

The NCUA board’s decision to merge the Temporary Corporate Credit Union Stabilization Fund (TCCUSF) into the National Credit Union Share Insurance Fund (NCUSIF) is a good idea.

The closure of the TCCUSF will reduce expenses, end contracts that at best perpetuate the continuation of misleading judgments, and create sorely needed transparency by simplifying the NCUA’s reporting.

More importantly, it should enable the NCUA to tie the financial results of the NCUSIF to real world events. What do I mean by that? Current practice involves projecting long term future facts to justify current expenditures factsthat simply don’t hold up when back-checked. Not even close.

This fresh start for the NCUSIF would also reinforce the NCUA’s primary fiduciary responsibility to credit union members. It is the members, after all, who send one cent of every insured share to fund the NCUSF, and for whose interests NCUA is thesteward.

Returning members’ money as quickly and as fully as possible should be the Board’s dominant priority.

Up to $2.4 Billion Of Your Members’ Money Is At Stake. Watch,Is The NCUA Finally Doing The Right Thing?

So, how much is due to your members? A lot more than NCUA staffers would like you to believe.

Make Your Voice Heard

The NCUA is accepting comments on the merger of the corporate bailout fund into the share insurance fund. The deadline is Sept. 5.

The merger of the TCCUSF and NCUSIF should allow for a distribution of a minimum of $1.8 billion and as much as $2.4 billion to credit union members in 2018. However, the NCUA staffers are making specious arguments to withholdalmost a billion dollars of your members’ money under the guise of risk management.

Today, all money in excess of the 1.30% equity ratio the regulator uses as its Normal Operating Level (NOL) must be paid back to credit unions in the form of a dividend. NCUA staffers are proposing to raise that ratio to 1.39% and tohold back funds in case the original assets of the TCCUSF which would now be a liability of the NCUSIF due to the merger do not perform as expected.

OK, sounds reasonable enough. Until one looks at the facts and does the math.

The justification for the increase is based on the same selective modeling that resulted in billions of excess reserves, unnecessary premiums, and overestimates of losses on legacy assets over the past seven years. Let’s dig into it. ContentMiddleAd

Hiding Behind a Wall of Words

To justify their proposal, the NCUA staffers presented the Board some 60 plus slides in my opinion creating more confusion for credit unions about financial judgments of the past nine years. This same pattern of multi-scenario modelingprojections, has been used to justify results that have proven time and again to have no connection to reality.

This pattern of significant erroneous loss projections is illustrated clearly in a nine-year table of the NCUSIF’s loss reserving activity compared with the reported net cash losses.

FACT: Throughout the Great Recession, the actual cash losses of the NCUSIF have only been a fraction of the reserves established at the prior year-end audit date. In 2009 and 2010 peak crisis years actual cash losses werejust 30% and 7.6% of the prior year-end audited reserves. (See graph below) By over-reserving, the NCUA not only charged credit unions unnecessary premium expense, but also demonstrated that its modeling and internal monitoring ofproblems are completely disconnected with real results.

I realize models are just that an attempt to understand different scenarios and chose the best paths today for an uncertain future. But with nine years of data, it’s clear that a new model is needed. If a credit union did this kind of modeling on its own loan loss reserves, there’s not a CPA in the country that would approve their statements.

FOLLOWING YEAR CASH LOSSES AS A PERCENTAGE OF LOSS RESERVE

Source: NCUA

Now, NCUA staffers want to use this same faulty reasoning to justify an increase of the NOL to 1.39%.

Let’s walk through the numbers using balances in both funds as of June 30, 2017. Today, the NCUSIF fund ratio is 1.26%. The NCUA’s own projections of a possible full-year loss of $26 million (versus actual midyear net income of $7.4million) won’t materially affect this level.

Adding the TCCUSF’s projected surplus to the NCUSIF’s current position of $13.026 billion gives a total balance of $16.0 billion. Using the NCUA’s own estimate of insured savings at year-end will result in a fund/insured share ratioof 1.47%, well above the current cap of 1.30%. At this fund size, each change of one basis point in the NOL ratio equates to approximately $109 million.

Therefore, staffers’ recommendation to increase in the NOL to 1.39% means holding back 13 basis points of TCCUSF surplus due to your members. That’s 4 basis points to meet the 1.30% current ceiling plus an additional 9 basis points for newcontingencies. This 9 basis point increase equals more than $980 billion (9 x $109 million).

Credit union members would only receive an estimated payout of 8 basis points (1.47%-1.39%), approximately $871 million. That would be about a third of the available TCCUSF recoveries transferred.

If credit unions received their total due 17 basis points above the current NOL of 1.26% they would receive approximately $2,400 for each $1.0 million of insured shares. Under the staff proposal, members will receive less than $900 foreach $1.0 million of insured shares. That’s a big difference.

Nine years of recent history has shown us that the NCUA’s models don’t match reality. They shouldn’t just keep relying on the same hoary projections that resulted in unnecessary premiums and billions in overestimates of losses forcredit unions during the corporate resolution to justify withholding members’ funds.

So, what’s wrong with reserving for contingencies? Nine years of recent history has shown that NCUA’s models don’t match reality. They shouldn’t just keep relying on the same hoary projections that resulted inunnecessary premiums and billions in overestimates of losses for credit unions during the corporate resolution to justify withholding members’ funds today.

From Insurance Fund to Slush Fund

So, what’s their motivation? The NCUSIF is an insurance fund, designed in 1980 to provide capital support to credit unions in financial distress. However, over the past nine years, the NCUA has changed the role of the NCUSIF from an insurance fundto a slush fund for their daily operating expenses.

Each year, the NCUA charges the NCUSIF for a portion of its operating expenses. This is called the overhead transfer rate (OTR). Between 2008 and 2016, the OTR that is the proportion of operating expenses charged the fund, jumped from 52% to 73.1%.

This resulted in the entire increase in the NCUA’s annual operating budget (which grew by $123 million between 2008 and 2016) being billed to the NCUSIF.

The NCUA’s progressive raises in the OTR have resulted in an operating expense ratio that has risen steadily from 20% in 2008 to 91% of the NCUSIF’s total income in 2016. This current expense burden leaves little or no margin to pay lossesor to increase retained earnings to maintain the NOL ratio at the pace of insured share growth.

To top it off, after taking increasing amounts of NCUSIF income each year for expense reimbursement, NCUA continually shows no accounting correlation between the loss provision expense and the actual cash losses reported by the fund.

In 2009 and 2010, NCUA charged premiums which increased the fund’s total income by $1.657 billion. These two crisis premiums created the highest loss reserve in the agency’s history at $1.225 billion a reserve so excessive it could have paid for all the actual cash losses not only the following six years ($435 million), but also for all the losses paid by the fund in its history.

And what did NCUA do with the fund’s net in excess of the 1.3% ceiling? It didn’t give it back to credit unions. Rather, $462 million was paid into the TCCUSF. In other words, a premium charged for one purpose was then transferred to anotherfund which had a completely separate function. That is, NCUA kept the funds for themselves.

$ NCUSIF OPERATING EXPENSE VS. OVERHEAD RATIO

Source: NCUA

NCUA’s premiums to pay for these erroneous loss provision expenses were pro-cyclical with the economic crisis. This meant credit unions were over-assessed with an unnecessary expense burden at the very time they were trying to recover.

NCUA now maintains they must increase the NOL to 1.39% to avoid these pro-cyclical assessments. However, as the analysis shows, the problem isn’t either timing or adequate fund balances; the real problem is that the NCUA is unable to align financialcosts with the real losses in the field.

The latest example is from 2016. The actual net cash losses were $12.2 million, or just 6% of the year-end loss reserve. According to NCUA’s 2016 annual report (page 125), these same models are still in use today with the same staffdoing the projections.

In the request to raise the NOL, NCUA staffers say they included modeling based on the Federal Reserve inputs for a moderate and severe recession. Their model projects a five-year insurance loss between $1,266.6 billion (adverse) and $1,965.8 billion(severely adverse). Compare these forecasts to the actual losses of the past nine years (2008-2016) which include the worst recession since the Great Depression: $1,033 billion.

But Aren’t The TCCUSF’s Legacy Assets Riskier?

I’ve been asked: doesn’t the merger with the TCCUSF put more risk on the NCUSIF? Aren’t the legacy assets of the corporate system different riskier than that of regular credit unions? Isn’t that how we got into thismess in the first place?

Once again let’s dig into the numbers to show how the legacy assets are actually performing and what that means for the merged funds.

The NCUA’s models have been no better and in fact are quite possibly worse than their performance on the retail side. As in the NCUSIF, the agency’s TCCUSF record is one of overestimating losses, underestimating the value ofassets taken, and not providing timely and detailed information from which individual claimants and shareholders could monitor events.

To really follow all the numbers, one must look at five corporate balance sheets (pre-conservatorship), financial statements for the subsequent AMEs (asset managed estates), four bridge corporates financials, the 13 NCUA Guaranteed Notes (NGN) trusts,legacy assets spreadsheets, the TCCUSF financials and various reports the NCUA has issued to try to tie all of these separate entities together.

Putting aside the utter opacity in NCUA’s handling of the all these interconnected TCCUSF entities (which underscores the wisdom of merging the funds to increase visibility), NCUA itself says its initial projections of losses on legacy assets werein error by at least $3.2 billion or as much as $6.0 billion (slide 9).

NCUA staff’s recommendation is to hold back 4 basis points, or about $435 million, for the NCUSIF’s assumption of the TCCUSF’s contingent guarantee of the NGN payments.

This contingency was reviewed by external auditors of the TCCUSF fund as recently as December 2016. The following statements are from the KPMG audit:

One fact cited to support this zero contingency in the audit is that legacy assets’ net realizable value exceeded the remaining balances due to the NGN holders by $2.4 billion at year-end. NCUA’s rights as liquidating agent wouldpermit them to use the AME’s residual interests in the trusts to pay off the NGNs.

The only uncertainty is whether cash flow from legacy assets will be sufficient to make the final payments in 2021. However, the NCUSIF has extensive cash reserves. The holdback of 4 basis points or $430 million is not only unnecessary but is completelyunsupported by the two most recent audits.

The goal today is to convince credit unions that they need to stand up to the staffers at NCUA and demand the return of their members’ money. Merging the two funds will shed much needed light on the NCUA’s management of the corporate resolutionand hopefully, bring the industry closer to putting the trauma of the Great Recession behind us.

There are a host of additional questions about NCUA’s management of the TCCUSF, such as the allocation of legal recoveries, the $1 billion taken as losses on non-securitized assets held by the failed corporate credit unions, or whatthe $1.046 billion in liquidation expenses were for. But that is for another article.

The goal today is to convince credit unions that they must act as owners by responding to the NCUA board’s request for comments. Merging the two funds will shed much needed light on the NCUA’s management of future corporate resolution transactions.It will end a workout that has now gone on for almost nine years.

In summary, encourage the NCUA board to:

Also Read

What’s $1.8 Billion Between Friends?

Is The NCUA Finally Doing The Right Thing?

Carpe Diem! NCUA Deadline Here For Comment On Bailout Funds Merger

Daily Dose Of Industry Insights

Stay informed, inspired, and connected with the latest trends and best practices in the credit union industry by subscribing to the free CreditUnions.com newsletter.

Share this Post

Latest Articles

Markets React To Consequential Announcements

Meet The Finalists For The 2026 Innovation Series: Data And Decision Intelligence

A New Product Playbook Is Driving Change At Premier Credit Union

Keep Reading

Related Posts

Markets React To Consequential Announcements

Financial Nihilism Is Real, But How Can Credit Unions Respond?

2026 Begins With Market Sentiment Similar To 2025

How To Build AI Strategy In Real Time (Part 1)

Marc RapportHow To Build AI Strategy In Real Time (Part 2)

Marc RapportChanges Are Why You Need Today’s Nacha Rulebook

View all posts in:

More on: