Where are the credit unions?

I’ve always believed that the key to happiness is telling the difference between problems you can and should solve versus problems that are outside your sphere of influence. I recently read a book that overwhelmed me with problems that feel unsolvable except for one.

As you read this blog, I hope you’ll consider answering this question when you’re done: am I wrong?

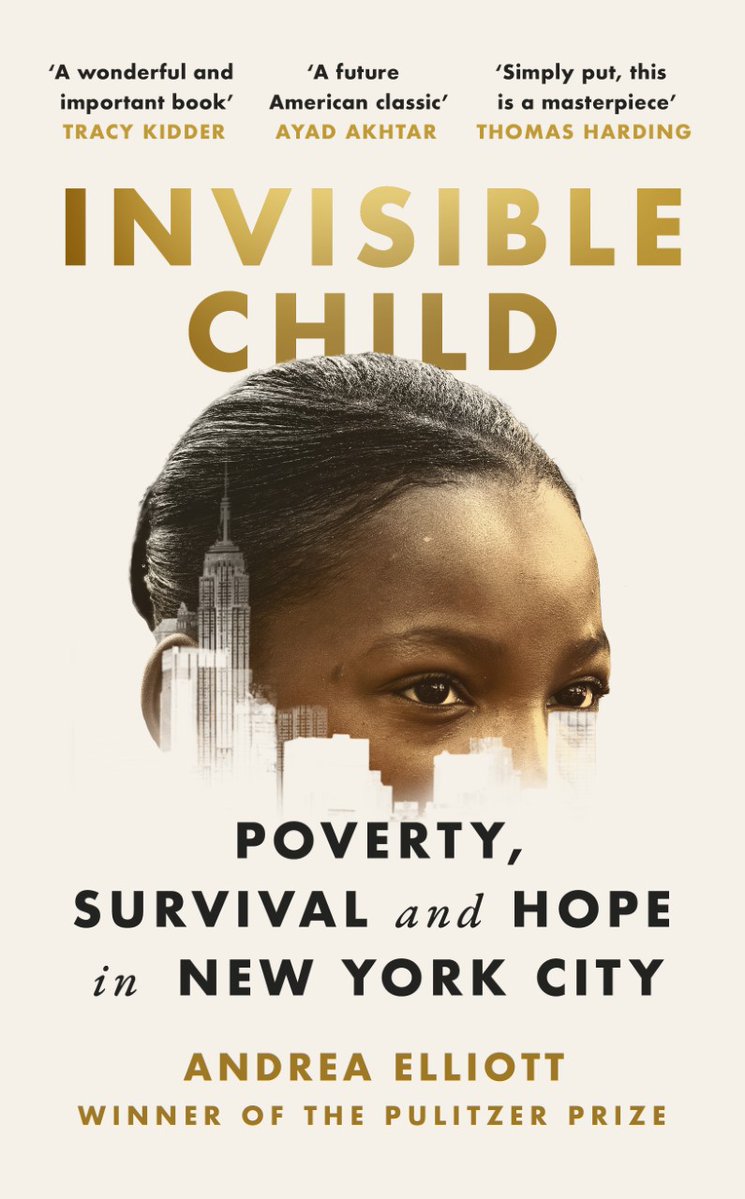

Invisible Child: Poverty, Survival Hope in an American City by Andrea Elliott represents journalism at its finest. Through years of reporting for the New York Times, and then personal research, Elliott follows one New York City family through the eyes of the oldest child, Dasani Coates. Named for aspirational water her mother saw in a supermarket but couldn’t dream of affording, Dasani spends her life taking care of not just her seven siblings but also at times her parents as their lives become more and more challenging.

Homeless since birth, she helps her mother shepherd her children between multiple shelters, schools, welfare and Child Protective Services offices, and eventually courtrooms. No strangers to adversity and childhood trauma themselves, her parents struggle with addiction, anger-management issues and prison records. To qualify for many of their benefits, the whole family must attend various state-mandated appointments and submit to frequent inspections.

This book won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction, and after reading it, it’s clear why. In addition to an incredibly detailed portrait of Dasani’s life and the life of her family, Elliott goes back multiple generations to trace the various traumas that contributed to the Coates family’s hardship. She presents a thorough reporting of the New York City metropolitan social services system and its repeated failures to provide services and funds that would have made major differences in Dasani’s life.

To be blunt, there is no lack of tragedy in this book, but the most upsetting elements for me were the repeated trusted adults in Dasani’s life who tried and failed to help her secure a better path. Along the way, the author describes social workers, teachers, and other authority figures who did their best to help Dasani and her family but were ultimately overwhelmed by the bureaucracy of the systems in which they are forced to work.

In an incredibly gripping passage, Dasani, her father and her seven brothers and sisters slowly begin to starve because their welfare cash and food stamps are in her mother’s name, attached to her EBT card, and her mother is nowhere to be found. To put it another way, her family has money and food stamps, but eight children, including a toddler, starve anyway because of a lack of access.

What? WHAT?!

This section was what finally woke me up and made me ask the question, how on Earth is there no mention of financial services in a book that’s more than 600 pages long and that dedicates at least half of its reporting to the various community services currently in place to help people of small means? How on Earth can a poverty-stricken family that qualifies for public benefits still starve because the small piece of plastic that allows them to access those benefits is in the pocket of a person who can’t be found?

What Is Our Industry’s Role?

Call it an occupational hazard, but questions kept floating through my mind as I read: Could credit unions have helped here? Are they helping already and it just weren’t covered in the book? Is there context I’m lacking that would help me understand our industry’s lack of representation here?

Welfare recipients have stable sources of income that are deposited on the same day of every month. While it is possible to deposit these funds into a bank or credit union account, many do not do so for a variety of reasons, including trust in their local financial organizations, unpaid debt, criminal records, and more.

I am not an expert on the technology that powers welfare-benefit distribution. I know nothing about the red tape and other details that probably make this an unattractive or perhaps impossible arena for credit unions to enter.

I am writing this blog because I read a well-researched, thoroughly documented book about how social services continuously failed to serve a poverty-stricken family those services were designed to help. I am saddened that financial services and credit unions in particular don’t even register as part of the conversation.

My hope is that someone in our industry can read this and explain why.

Are credit unions working in this space? If not, why? What are the barriers? If so, what are you doing and do you see an impact on your members and communities?

Am I totally reading this wrong? Excellent that’s an opportunity to learn, and I would appreciate the education.

Life is too short to not do what we can, and unlike the overwhelmed civil servants in this book, we work for an industry that allows us to take our values and passion for service to work every day.

The credit union employees I know aren’t focused on actions for the sake of themselves they care about identifying and amplifying their impact on the members and communities they serve.

If you haven’t read this book, please do. If it’s not in your budget or in your local library, email me at JDavis@callahan.com and I will Venmo you. If you don’t want to read the book, but you’re willing to discuss this, please shoot me an email and hopefully we can find time to talk.

I look forward to hearing from you and please, call me Jen.

Pulitzer Prize-Winning Book Raises Questions For Credit Unions

Where are the credit unions?

I’ve always believed that the key to happiness is telling the difference between problems you can and should solve versus problems that are outside your sphere of influence. I recently read a book that overwhelmed me with problems that feel unsolvable except for one.

As you read this blog, I hope you’ll consider answering this question when you’re done: am I wrong?

Invisible Child: Poverty, Survival Hope in an American City by Andrea Elliott represents journalism at its finest. Through years of reporting for the New York Times, and then personal research, Elliott follows one New York City family through the eyes of the oldest child, Dasani Coates. Named for aspirational water her mother saw in a supermarket but couldn’t dream of affording, Dasani spends her life taking care of not just her seven siblings but also at times her parents as their lives become more and more challenging.

Homeless since birth, she helps her mother shepherd her children between multiple shelters, schools, welfare and Child Protective Services offices, and eventually courtrooms. No strangers to adversity and childhood trauma themselves, her parents struggle with addiction, anger-management issues and prison records. To qualify for many of their benefits, the whole family must attend various state-mandated appointments and submit to frequent inspections.

This book won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction, and after reading it, it’s clear why. In addition to an incredibly detailed portrait of Dasani’s life and the life of her family, Elliott goes back multiple generations to trace the various traumas that contributed to the Coates family’s hardship. She presents a thorough reporting of the New York City metropolitan social services system and its repeated failures to provide services and funds that would have made major differences in Dasani’s life.

To be blunt, there is no lack of tragedy in this book, but the most upsetting elements for me were the repeated trusted adults in Dasani’s life who tried and failed to help her secure a better path. Along the way, the author describes social workers, teachers, and other authority figures who did their best to help Dasani and her family but were ultimately overwhelmed by the bureaucracy of the systems in which they are forced to work.

In an incredibly gripping passage, Dasani, her father and her seven brothers and sisters slowly begin to starve because their welfare cash and food stamps are in her mother’s name, attached to her EBT card, and her mother is nowhere to be found. To put it another way, her family has money and food stamps, but eight children, including a toddler, starve anyway because of a lack of access.

What? WHAT?!

This section was what finally woke me up and made me ask the question, how on Earth is there no mention of financial services in a book that’s more than 600 pages long and that dedicates at least half of its reporting to the various community services currently in place to help people of small means? How on Earth can a poverty-stricken family that qualifies for public benefits still starve because the small piece of plastic that allows them to access those benefits is in the pocket of a person who can’t be found?

What Is Our Industry’s Role?

Call it an occupational hazard, but questions kept floating through my mind as I read: Could credit unions have helped here? Are they helping already and it just weren’t covered in the book? Is there context I’m lacking that would help me understand our industry’s lack of representation here?

Welfare recipients have stable sources of income that are deposited on the same day of every month. While it is possible to deposit these funds into a bank or credit union account, many do not do so for a variety of reasons, including trust in their local financial organizations, unpaid debt, criminal records, and more.

I am not an expert on the technology that powers welfare-benefit distribution. I know nothing about the red tape and other details that probably make this an unattractive or perhaps impossible arena for credit unions to enter.

I am writing this blog because I read a well-researched, thoroughly documented book about how social services continuously failed to serve a poverty-stricken family those services were designed to help. I am saddened that financial services and credit unions in particular don’t even register as part of the conversation.

My hope is that someone in our industry can read this and explain why.

Are credit unions working in this space? If not, why? What are the barriers? If so, what are you doing and do you see an impact on your members and communities?

Am I totally reading this wrong? Excellent that’s an opportunity to learn, and I would appreciate the education.

Life is too short to not do what we can, and unlike the overwhelmed civil servants in this book, we work for an industry that allows us to take our values and passion for service to work every day.

The credit union employees I know aren’t focused on actions for the sake of themselves they care about identifying and amplifying their impact on the members and communities they serve.

If you haven’t read this book, please do. If it’s not in your budget or in your local library, email me at JDavis@callahan.com and I will Venmo you. If you don’t want to read the book, but you’re willing to discuss this, please shoot me an email and hopefully we can find time to talk.

I look forward to hearing from you and please, call me Jen.

Share this Post

Latest Articles

Americans Report Favorable Views On Small Business

Fed Leaders Hope To Avoid Repeating The Mistakes Of The 1970s

Think AI Is Big Now? Give It A Year.

Keep Reading

Related Posts

Americans Report Favorable Views On Small Business

Fed Leaders Hope To Avoid Repeating The Mistakes Of The 1970s

Think AI Is Big Now? Give It A Year.

Opportunities Abound For Veterans At A Kentucky Credit Union

Aaron PassmanThe Power Of Business Lending And Services

Marc RapportEveryone’s A Risk Manager At Logix FCU

Sharon SimpsonView all posts in:

More on: